Decidability

But first, poetry. Because it is beautiful and right and it is always a good time to ruminate Dickinson.

This is my letter to the World

That never wrote to Me —

The simple news that Nature told —

With tender majestyHer message is committed

To hands I cannot see —

For love of Her — Sweet — countrymen —

Judge tenderly — of Me— “This is my letter to the World,” Emily Dickinson

As you will soon learn, the challenge in decidability is finding a systematic way to assess whether certain problems can be solved algorithmically. You are looking for an oracle, so to speak. But unlike Dickinson, your truths are not the kind of revelations you can get from the unseen oracle of nature.

And you must not beg for your truths to be judged tenderly either, because your truths come from oracles are backed by universal definitions that are just as beautiful and right.

Said Definitions

Turing machine: A Turing machine is a theoretical computational device used to simulate algorithms and perform computations. It consists of an infinitely long tape, a read/write head, and a finite set of states.

Recursive Language: In the context of Turing machines, a language is “recursive” when a Turing machine can reliably determine if a given string belongs to that language. The machine always provides a clear answer - either accepting or rejecting - for any input string without getting stuck in an infinite loop.

Recursively Enumerable Language: On the other hand, a “recursively enumerable” language can be recognized by a Turing machine, but there’s a caveat. The machine can accept and halt for strings within the language, but it may not halt for strings outside the language, potentially getting stuck in an infinite loop without providing a definitive answer.

Decidable Language: A “decidable” language is a subtype of recursive language. Here, a Turing machine can fully recognize the language. It offers a clear and definitive answer for every input string, whether it belongs to the language or not. All decidable languages are also considered recursive languages.

Partially Decidable Language: Conversely, a “partially decidable” language, also known as “recursively enumerable,” is a bit more flexible. It can be recognized by a Turing machine, accepting and halting for strings within the language. However, it might not always halt for strings outside the language, unable to provide a clear rejection.

Undecidable Language: An “undecidable” language is the opposite of a decidable language. It cannot be fully recognized by a Turing machine. Some undecidable languages may still be partially decidable (recursively enumerable), meaning they can recognize elements within the language but not always reject non-members. Others are so complex that they’re not even partially decidable, and there is no Turing machine capable of handling them.

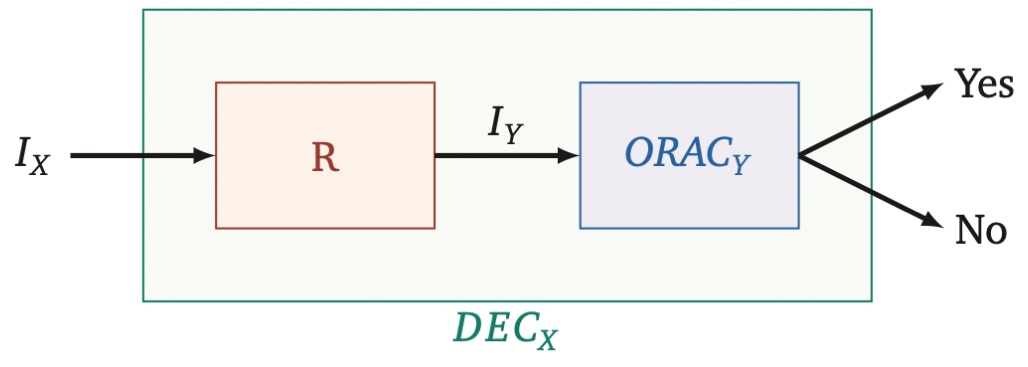

Oracles and reductions

Picture reductions in the world of computability as the crafty translators of complex riddles into simpler puzzles. Just as Dickinson interpreted the subtle whispers of the natural world, reductions allow us to interpret complex problems (take, for example a Problem X) through the lens of simpler ones (example Problem Y).

Here’s the nifty trick: if we can solve Problem Y, then Problem X starts to make sense. It’s a bit like reading a poem - first, it seems orphic, but once you grasp the theme, the rest falls into place. In our computability waltz, this is choreographed as X => Y.

This reduction process is a cornerstone in decidability.

Understanding the Halting Problem: An Intuitive Approach

The Halting Problem in computer science is like trying to predict the outcome of an endlessly diverse set of stories. Each story represents a different program and its input. The question at the heart of the Halting Problem is simple yet profound: can we create a master storyteller (an algorithm) that can predict the end of every story, whether it concludes (halts) or continues forever?

Unfortunately, this master storyteller doesn’t exist. Why? Because for every algorithm we create to predict the endings, there’s always a story that it can’t predict. This is not just a tough problem – it’s an impossible one. There’s no algorithm that can solve the Halting Problem for all possible program-input pairs.

Using Reduction to Prove Undecidability of the Halting problem

Now here is why:

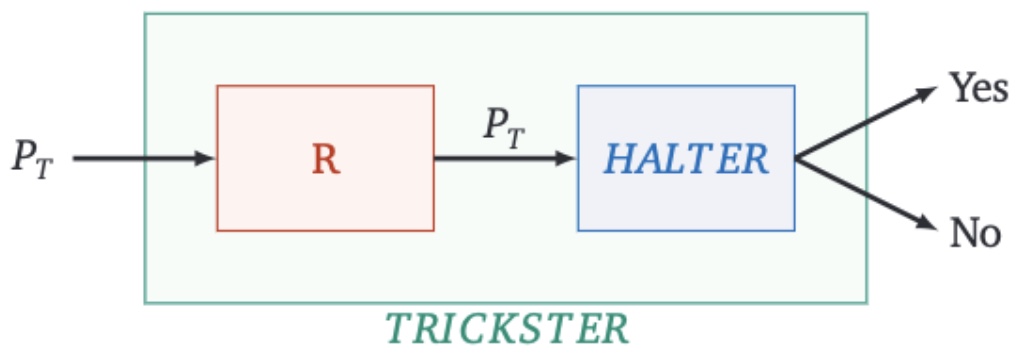

Our initial Assumption: Let’s start by assuming we have a program named Halter. This program, by our assumption, can solve the Halting Problem. That means for any given program and its input, Halter can correctly determine whether the program halts or runs indefinitely.

Creating Trickster: Next, we introduce a new program called Trickster. Trickster is designed to take another program as its input. Now, here’s the twist:

- If Halter predicts that the input program will halt, Trickster will continue to run forever.

- Conversely, if Halter predicts that the input program will run indefinitely, Trickster will stop.

The Paradox: Let’s put Trickster to the test by feeding it to Halter. We are now asking Halter to predict what Trickster will do.

- If Halter says, “Trickster halts,” then it should run forever according to Trickster’s design. But this contradicts Halter’s prediction.

- If Halter says, “Trickster runs forever,” then Trickster should halt. Again, this contradicts Halter’s prediction.

Conclusion: This contradiction shows that our initial assumption must be false. No such program like Halter can exist, as it leads to a logical impossibility. This proof by contradiction, using the concept of reduction (reducing the Halting Problem to the behavior of Trickster), demonstrates that the Halting Problem is undecidable.

But there are still decidable problems

But before you go around searching for oracles, a dash of optimism– there are decidable problems, of course. You have [hopefully] been solving them for the last several weeks. Some easy checks before going in search of oracles:

-

Algorithm Existence: Check if there exists an algorithm that can always provide a definitive yes or no answer for any instance of the problem. If such an algorithm exists, the problem is decidable.

-

Halting on All Inputs: Ensure that for every possible input, the algorithm halts (i.e., it does not run indefinitely) and provides a clear answer.

-

Reference to Known Decidable Problems: Often, it helps to compare the problem in question to a list of known decidable problems. If it closely resembles or can be reduced to a known decidable problem, it’s likely decidable.

-

Logical Analysis: Some problems can be shown to be decidable through logical reasoning or mathematical proof.

Examples of known decidable problems

-

Path Existence in Graphs: Determining if there is a path between two nodes in a graph.

-

Sorting Problems: Determining if a list can be sorted in a certain way (e.g., in ascending order).

-

Prime Number Identification: Determining if a given number is prime.

-

Reachability in Finite Automata: Determining if a certain state in a finite automaton is reachable from a given starting state.

-

Language Membership for Regular Languages: Determining if a given string is part of a specific regular language.

-

Palindrome Detection: Determining if a given string is a palindrome.

Additional Resources

- Textbooks

- Erickson, Jeff. Algorithms

- Sipser, Michael. Introduction to the Theory of Computation

- Chapter 5 - Reducibility

- Sariel’s Lecture 9