Dynamic Programming

Dynamic programming(DP) is an algorithmic technique of recursively dividing the problem into smaller subproblems and solving the subproblems while memoizing the results to solve the original problem. If this sounds similar to divide and conquer, then you are right. The only thing that distinguishes DP from divide and conquer is the memoization of subproblems. DP approach can be applied when the following two conditions hold:

- The problem can be solved by combining the solutions to smaller subproblems.

- The subproblems overlap.

The point of DP is to memoize the overlapping subproblems so that you don’t have to solve the same subproblem multiple times, which can greatly reduce the time complexity.

DP Example

To get a sense, let’s consider a classic example of Fibonacci sequence. The $n$th Fibonacci number is defined as the following.

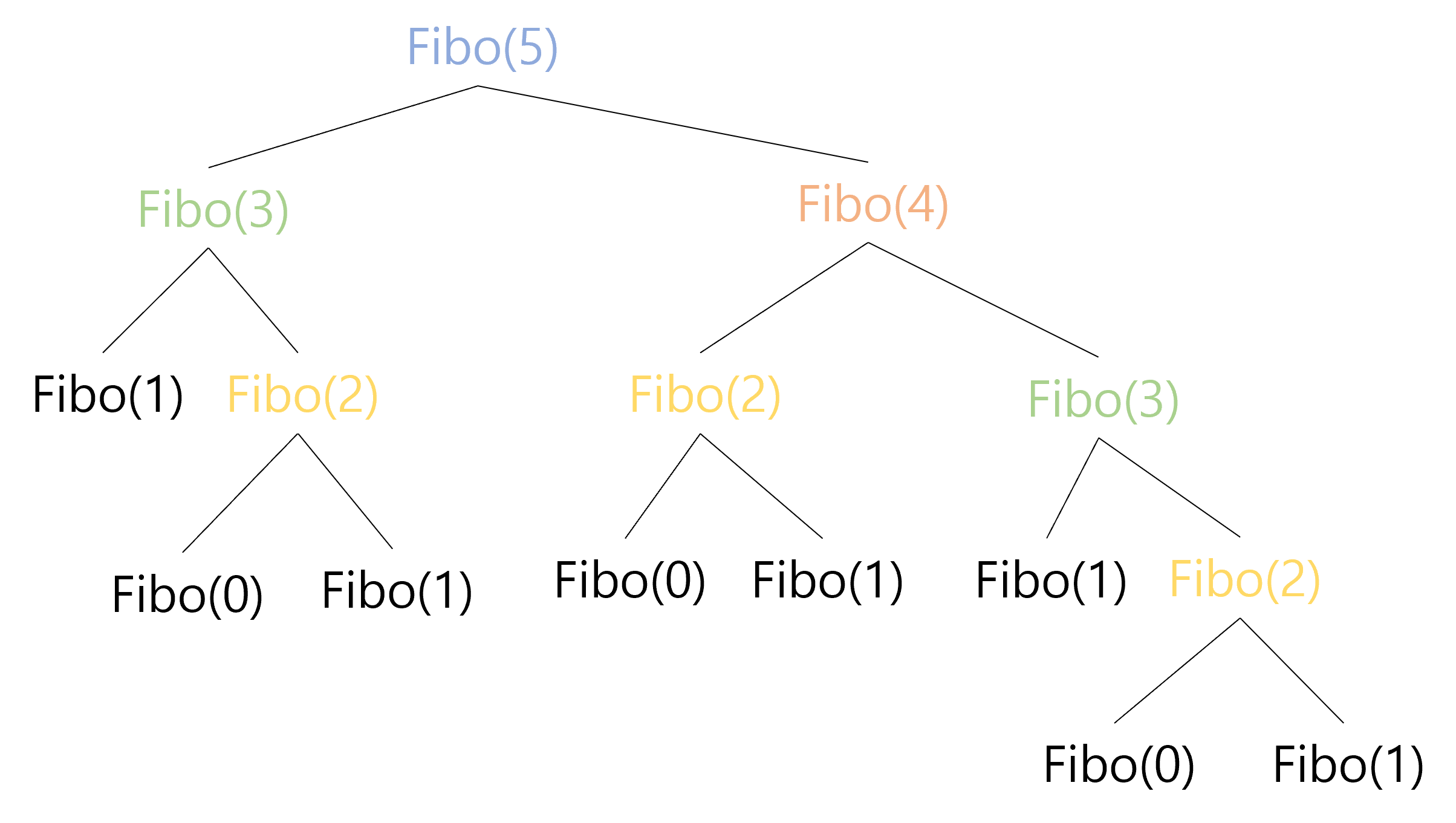

\[Fibo(n)= \begin{cases} 0 &\text{if }n=0\\ 1 &\text{if }n=1\\ Fibo(n-1)+Fibo(n-2) &\text{otherwise} \end{cases}\]To find the $n$th Fibonacci number, we need to add the the $(n-1)$th and the $(n-2)$th Fibonacci number. Then again, to get the $(n-1)$ Fibonacci number, we need $(n-2)$th and $(n-3)$th, for $(n-2)$th we need $(n-3)$th and $(n-4)$th, and so on. The following figure is the recursion tree for $Fibo(5)$.

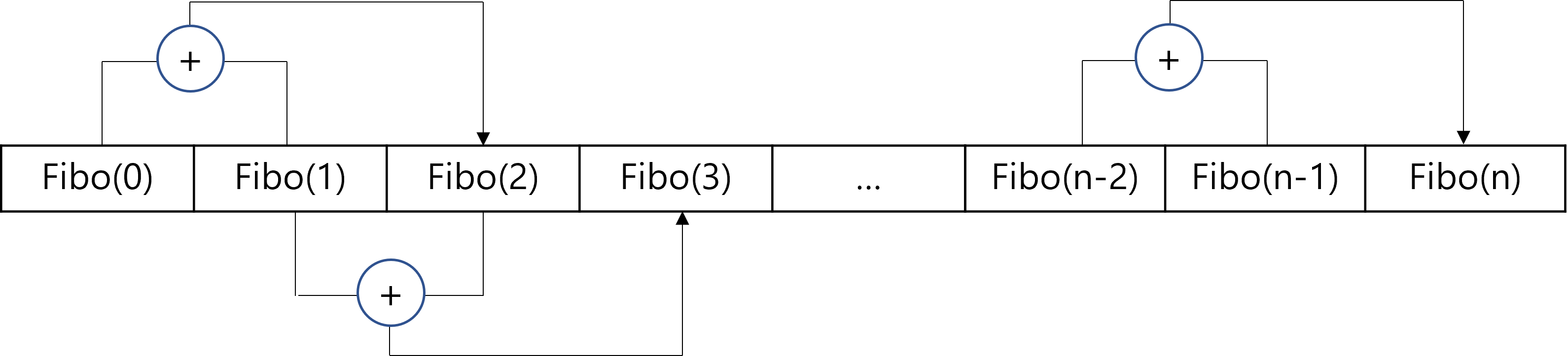

As you can observe, solving $Fibo(5)$ involves solving the same subproblems multiple times; there are 2 occurrences of $Fibo(3)$ and 3 occurrences of $Fibo(2)$ in the recursion tree. We can imagine that as as $n$ increases, we would have even more occurrences of overlapping subproblems. However, solving the subproblems from scratch - that is, expanding the whole recurence tree all the way down to the base cases - is inefficient. After all, $Fibo(k)$ for a constant $k$ is a constant integer. Therefore, once we compute $Fibo(k)$, we can memoize the corresponding constant and directly access the value without expanding the recursion everytime we need the value of $Fibo(k)$ in the future. Based on this idea, we can solve $Fibo(n)$ in $O(n)$ time by filling a 1D array, as appears in the following figure.

We start by filling out the first two cells which are the base cases, and then we simply add two consecutive cells to find the value for the next cell. Since we memoize the computed value in the array, we can directly access the value without recomputing it, whenever we need the value. We can simply repeat adding two cells and storing the value in the next cell until we reach the $n$th cell, which would contain the value of $Fibo(n)$.

Deriving DP from Recurrence

The key to writing a DP solution is finding an appropriate recurrence. Once you have a recurrence, the rest - the memoization data structure, the order of evaluation, time complexity, return value, etc - often can be easily derived. As an example, consider the following recurrence named $SomeRandomRecurrence$, abbreviated as $SRR$.

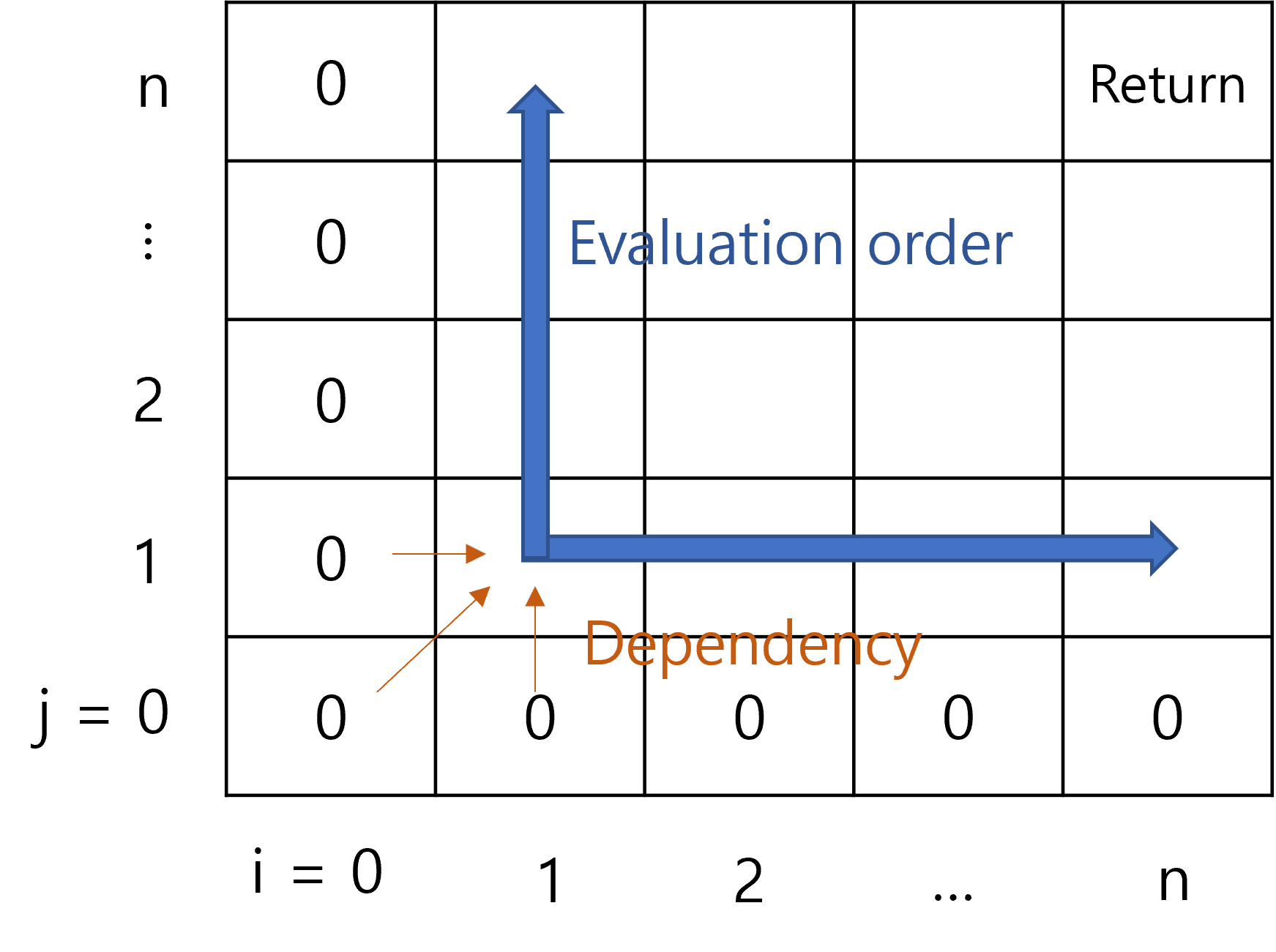

\[SRR(i, j)= \begin{cases} 0 &\text{if }i=0 \text{ or } j=0\\ SRR(i-1, j-1)+1 &\text{if } SomeRandomCondition\\ \max(SRR(i-1,j),SRR(i,j-1) )&\text{otherwise} \end{cases}\]Let’s suppose we want to return $SRR(n,n)$ at the end. Since we do not have any description of the recurrence, we don’t even know what problem we are solving. However, we can still figure out an appropriate memoization data structure and the evaluation order. Observe that $SRR(i,j)$ only depends on $SRR(i-1,j)$, $SRR(i,j-1)$, and $SRR(i-1,j-1)$. Since $SRR(n,n)$ would have no dependency on $SRR$ with indices greater than $n$, we are only interested in $SRR(i,j)$ where the parameters $i, j$ ranges from $0$ to $n$. We have $n^2$ different pairs of parameters, or in other words $n^2$ different subproblems, which means a 2D array would be appropriate as the data structure. Also, it is obvious that the evaluation order would be from lower to higher index, since we need to know the values in lower indices to find the values for higher indices.

Longest increasing Subsequence

Our very own Jeep Kaewla has created the following video explainer of the LIS problem:

Additional Resources

- Textbooks

- Erickson, Jeff. Algorithms

- Skiena, Steven. The Algorithms Design Manual

- Chapter 10.1 - Caching vs. Computation

- Chapter 10.3 - Longest Increasing Subsequence

- Cormen, Thomas, et al. Algorithms (Forth Edition)

- Chapter 14 - Dynamic Programming

- Sariel’s Lecture 13